Yes, You Can Go Glamping in Antarctica

You expect ice and adventure on an expedition to Antarctica. But five-star food? That’s just one of the surprises in store for Ben Mack.

“Stand proud and walk confidently!” shouts Philippe, one of three mountain guides waiting nearby as I crawl around a narrow ledge of rock as rough as sandpaper, with solid ice just metres below.

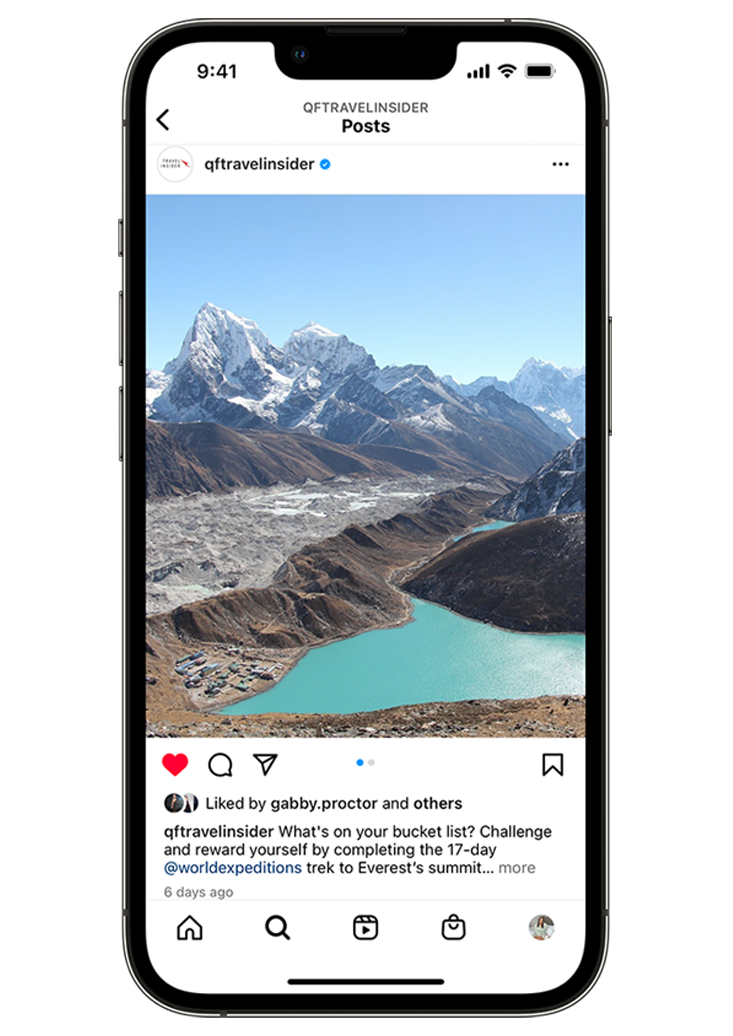

The wind is so loud it’s a roar. Feeling faint, I step off the ledge. “It’s the unknown we’re afraid of,” says Philippe later, after I’m lowered safely on a light-blue rope that’s attached to my snug harness. My measured descent of Snowbird Mountain – more than 71 degrees south latitude – is only one of the thrills on my expedition to Antarctica with White Desert.

The South Africa-based outfit flies to remote (even by Antarctic standards) Queen Maud Land in an Airbus A340 or Gulfstream 550 but only takes up to 24 adventurers at a time – the rest of the space on the plane is filled by scientists, cargo and fuel. With an ethos of “leave no trace” and having been net zero carbon for several years, as co-founder Patrick Woodhead tells me on the 5.5-hour flight south, White Desert runs three camps where guests can stay for a day, a week or longer during the Antarctic summer.

“Antarctica is a very empowering place to be,” says Woodhead, explaining that while thousands of people visit every year, “about 99 per cent” take a cruise. Only a few make the trip to the interior where his company has its camps. “It’s also scary. But mainly beautiful.”

I quickly realise how right he is while staying at Echo, its newest luxury camp, for seven days. The outpost features six heated, igloo-like, solar-powered pods (in summer it’s light here almost 24 hours a day), with king-sized beds, plenty of warm blankets and huge, curved windows that frame snowy expanses and frozen lakes, which stretch for dozens of kilometres into the distance until hitting dark mountains so jagged they look like dragon’s teeth.

Perhaps a sister of the White Witch of Narnia – who also covered her realm in eternal ice and snow – lives in those mountains, I think. The entrance to her lair is no doubt the nunatak (the top of a mountain sticking out of an ice field or glacier) named “Cheesegrater” by the team; I explore it on the first full day of my trip. It certainly looks like it belongs in a fantasy story, as well as being intimidating. Sunlight has heated the pockmarked rock (hence the name) and melted all of the surrounding snow, creating a large “scoop” of towering ice cliffs so high that the sun is blocked out when I stand at its base.

South polar skua seabirds occasionally fly overhead and one of the guides tells us they have nests nearby. There’s no sign of a witch; perhaps the unpredictable wind, which can suddenly become a shiver-inducing gale then just as suddenly stop, has convinced her to stay indoors.

But maybe she’s enjoying the same food as we are at Echo. Chefs Jenna and Sarah whip up breakfast, lunch and dinner using ingredients brought on the same plane I arrived on, while others come from an ice cave they use to store food outside the spacious, well-lit kitchen. “There’s a whole lot of maths involved,” explains Jenna about balancing sustainability with making sure the guests have enough to eat. “We also only use quality ingredients – we take no shortcuts.”

It shows. I’m amazed that despite being in such a remote place, the buffet breakfasts are like those at a five-star hotel. Jenna and Sarah even cook omelettes made to order – I try one and it’s among the best I’ve ever eaten, the gooey cheese melted perfectly. For lunch I tuck into roast beef and aubergine wraps with Greek pesto, while dinner is chicken wrapped in bacon with gorgonzola salad and potatoes. Early evening canapés include salmon and caviar and a seemingly endless supply of Laurent-Perrier champagne or a Cape Town-brewed beer appropriately named “Shackleton” in honour of the explorer.

Delicious as the food is, much of what’s not eaten is reused. It’s only the tip of the sustainability iceberg. I shower in hot water that’s sourced from melted snow – and look out to the cinematic landscape while doing so. I’m told by staff that all waste, including from the toilets, is returned to Cape Town.

White Desert’s guests usually arrive and depart at the same time but it’s not a guided tour. Doing your own thing is completely fine. Daily adventures include hiking, riding orange “fatbikes” fitted with special studded tyres across the icy terrain or crosscountry skiing. But a guide will almost always accompany visitors when they leave camp.

I’m glad to have a guide with me one afternoon when I come upon a crevasse. It’s only a metre or so across but looking down into it, the whites and blues of the ice give way to impenetrable blackness. I would not be getting out of it if I fell in, which is why I call out “HELP!” when I feel myself slipping in. A guide, Frederic, pulls me to safety in the blink of an eye – good thing I’m wearing a harness for him to yank.

“Antarctica attracts adventurers from all over the globe,” says Woodhead, a polar explorer himself, and it shows in our group. Among my cohort are Alex and Mina, a father and uni-student daughter from California using the trip as a bonding opportunity. Liz is from London and works in PR. She tells all of us during a dinner that includes duck with honey and Dijon mustard sauce that she once kissed David Beckham.

“Being in Antarctica’s a dream I’ve had since I was a child,” says Alex, adding that he’s been chatting with White Desert for five years to make his dream a reality. “It really has that sense of being off-world.” Mina tells me she plans on making a video game based on the surreal experience.

The surrealness cannot be overstated. One day we climb to the top of Cheesegrater to find the rock and sand flecked with nuggets of quartz, mica and feldspar. There’s so much that it sparkles like an enormous jewel left behind by a giant.

If the giant dropped their jewel, they also spilled a lot of sugar – the snow looks just like the sweet stuff when it twinkles in the sun. My imagination runs riot but another guest, named Sarah, who runs a high-end travel agency, is more pragmatic: “There’s an intensity of the moment that forces you to be present.”

Like any explorer, my skills are tested. On one occasion, I’m tied with another guest to a guide so we don’t get separated or fall and we scramble up rocky terrain to summit a nunatak called Shark Fin. On another, I use ice axes and crampons to scale walls of ice, which leaves my arms sore but I chat excitedly with my fellow guests and staff for the est of the trip about how exciting and unique it was. The activities are so numerous that it’s difficult to process one before I’m kitting up for the next.

Speaking of kit: I find I’m dressed more than adequately – I even sweat climbing Cheesegrater. Most of my gear, such as thermal pants and tops, down jackets and hiking boots that crampons can be attached to, I had to bring myself, using a list of recommended items White Desert sent me before the trip. Other pieces of equipment, like a polar jacket, ultra-thick Baffin boots that keep your feet warm when standing still and a helmet (required for many activities in case of slipping on the ice or falling rocks) has been lent to me by the company.

I may be in Antarctica but it’s not as cold as I had imagined. Most days it’s only a few degrees below 0°C, though the wind – stronger near the tops of nunataks – can make it feel colder.

The activities are all incredible but it’s the unplanned moments that really make for a memorable adventure. An impromptu game of table tennis with the guides, using the dining table, lasts late into one evening. Helping chefs Jenna and Sarah in the kitchen and learning how the camp operates is as fun as it is rewarding.

Being in such a rarely visited part of an already rarely visited continent is supposed to be once-in-a-lifetime. But on the flight back to Cape Town, I’m plotting how to get a job in the Echo kitchen so I can go back.

Start planning now

SEE ALSO: 21 of the Most Amazing Glamping and Off-Grid Stays in NSW

Image credit: Kelvin Trautman, Andrew Macdonald, Ben Mack