How to See the World’s Most Amazing Natural Phenomena

Whether it’s the Northern Lights viewed from the wilds of Iceland, glowing waves that lap at your feet in the Maldives or China’s rainbow-hued mountains, the world is full of incredible natural phenomena that have to be seen to be believed. We’ve created the ultimate guide on where, when and how to best experience the earth’s greatest wonders.

Abraham Lake

1/35WHERE: Alberta, Canada

WHEN: December to March when the lake is most likely to be frozen

To the uninitiated this looks like a lake filled with the kind of surreal jellyfish you only see in animated movies. But what you’re actually seeing is frozen gas bubbles – Alberta’s Lake Abraham has a high density of dead organic materials and the result is that in winter bubbles of frozen methane form to create this enchanting view. The safet way to approach is on a guided tour, wearing ice cleats.

Image credit: Alamy Stock Photo

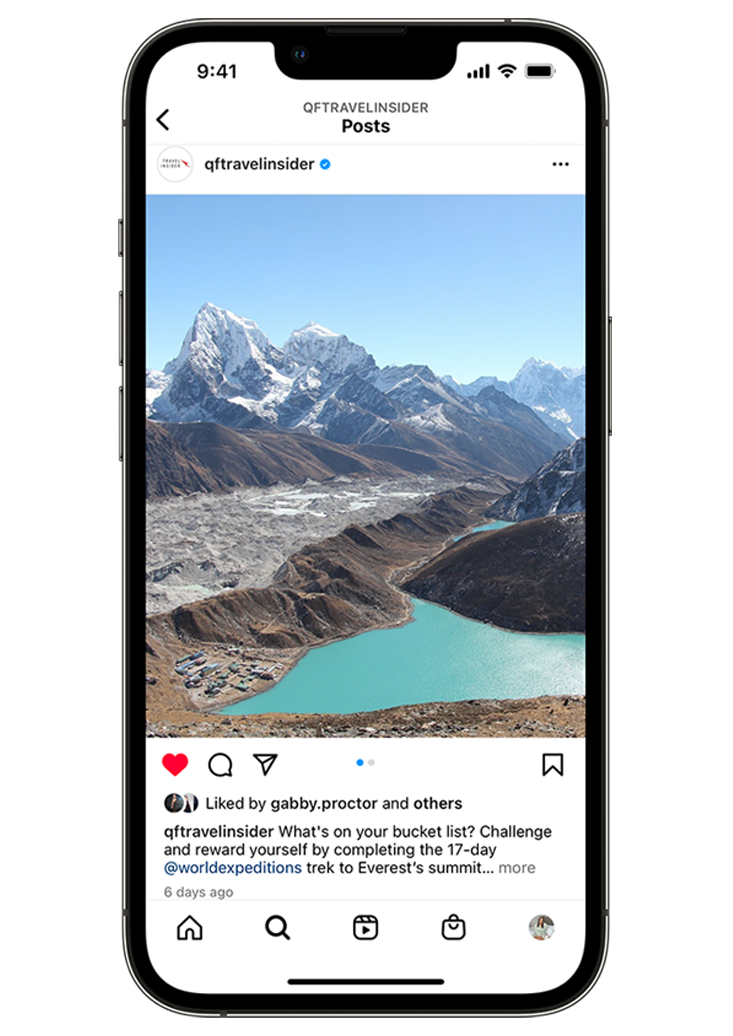

Aurora Borealis

2/35WHERE: Iceland, Finland, Norway, Canada or Alaska

WHEN: December to March

Gaseous particles colliding in the sky create the most amazing lightshow you’ll ever see. The colours change – green, yellow and blue are among the most common aurora shades – and the movement varies, too. Sometimes you’ll see a quick flash, other times there’s a soft, long glow along the horizon and often they dance before your eyes. You’re never guaranteed to see the Northern Lights, but your best chance is to go as far north as possible.

Image credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Aurora Australis

3/35WHERE: Antarcica, Tasmania, southern New Zealand and South America’s most southerly city, Ushuaia, Argentina

WHEN: Year-round, though the longer nights during winter months provide more opportunity

Aurora borealis has an exact counterpart in the Southern Hemisphere, aurora australis. Due to larger areas of uninhabited land close to the South Pole, the lights of the aurora australis are even more elusive to spot than their Northern Hemisphere counterparts. The higher you climb, the higher the chance you'll see the lights: Tasmania's Mount Wellington and New Zealand's Lake Tekapo are two of the best viewing spots.

Image credit: Kittisun Kittayacharoenpong

Rainbow Mountains

4/35WHERE: Zhangye, China

WHEN: Year round, best time to visit is June to September

For millennia, the Rainbow Mountains have been the canvas for an organic artwork, thanks to changes in the mineral make-up of the layers of sandstone that are the peaks’ base material, leading to the unexpected palette of colours. The mountain range is part of the Zhangye Danxia Landform Geological Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in China’s north-western Gansu province.

Image credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Blood Falls

5/35WHERE: McMurdo Dry Valleys region of Antarctica

WHEN: Year-round

The sight of crimson liquid gushing out over crisp white snow is downright creepy. The red rush that flows from the aptly named Blood Falls is not so sinister, however. It’s actually a combination of salt water, iron and bacteria rising from underground before being exposed to oxygen at the surface. Visitors must board a cruise ship visiting Antarctica’s Ross Sea in order to see it.

Image credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Giant’s Causeway

6/35WHERE: Northern Ireland

WHEN: Year-round, though you’ll get the best photographs at sunset at spring and autumn

Basalt columns are geological phenomena that form as a result of the cooling and cracking of thick lava. The famous Giant’s Causeway on the coast of Northern Ireland is one of the most beautiful examples: an estimated 40,000 mostly hexagonal columns of varying heights rise out of the Atlantic Ocean like some kind of real-life M.C. Escher staircase. It's free to stroll around, though there is a fee to enter the visitors 'centre.

Bioluminescent waves

7/35WHERE: Maldives

WHEN: December to April

Imagine being on a beach at night and seeing bright blue, glowing waves rolling towards you. This is known as bioluminescence and it’s caused by ostracod (crustaceans). One of the best places to spot bioluminescent waves is in the Maldives but similar activity can be seen in other parts of the world, such as the Caribbean and California.

Image credit: Getty Images/iStockphoto

Lake Hillier

8/35WHERE: Middle Island, Western Australia

WHEN: Year-round

Nestled photogenically behind a fringe of white sand on Middle Island, 11 kilometres off the south-east coast of Western Australia, Lake Hillier isn’t a place you’d chance upon on a road trip. But its startling bubblegum hue, best seen from the sky on a bright, sunny afternoon or via one of the limited number of cruises to this protected spot in the Recherche Archipelago, makes this 600-metre-long strip of surprise worth a detour.

Image credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Great Blue Hole

9/35WHERE: Belize

WHEN: Year-round

Generally speaking, sinkholes form in the ground when the earth is weakened by water that cannot be drained. “Blue holes” are thought to be massive submarine sinkholes that were formed during the Ice Ages and are now filled with water. One of the most popular examples is the Great Blue Hole in Belize, which is more than 300 metres in diameter and 125 metres deep. Confident dives can take the plunge into its centre; landlubbers can take a charter boat or light aircraft tour from several departure points on the mainland.

Image credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Flowering bluebells

10/35WHERE: Britain

WHEN: Late April to early May

Come spring, forests and meadows around Britain are carpeted with electric blue flowers named bluebells. The springtime bluebell season is an antidote to the winter blues and the show can be seen right around the country. The Woodland Trust has a Bluebell Watch where eager spotters can post their sightings, as well as maps displaying the annual bluebell spread.

Image credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Red crab migration

11/35WHERE: Christmas Island

WHEN: October to November

The 135 square kilometres that make up Christmas Island are home to an estimated 40-50 million red crabs. In the wet season, they migrate en masse to the beaches to release their eggs into the sea. While spawning dates can vary, the Christmas Island Tourism Association posts estimated dates on their site for visitors planning to witness the spectacle first-hand.

Image credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Coral spawning

12/35WHERE: Great Barrier Reef

WHEN: November to December

A colourful underwater blizzard is caused by the mass spawning of coral as it rises from the ocean floor. Spawning season in the Great Barrier Reef is typically , however it doesn’t happen at once and times can vary depending location. Keen to see it? Contact a local dive operator to discuss their packages for viewing.

Fairy circles

13/35WHERE: Namibia and Australia

WHEN: Year-round, though their estimated life cycle is anywhere between 30 and 60 years.

What appear to be giant polkadots scattered all over the ground are actually circular patches of barren land that can measure up to 15 metres diameter. The exact cause of them is a bit of a mystery but one theory is that they’re due to plant organisms clustering to make best use of available resources. Fairy circles were first discovered in arid regions of Namib Desert and in 2016 just outside the Western Australian town of Newman in 2014.

Image credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Flowering desert

14/35WHERE: Chile

WHEN: Followng extensive rainfall

The 105,000-square-kilometre Atacama Desert is the driest non-polar region in the world, thanks to its location between two mountain ranges and the heavy dry winds that blow through them. So when the landscape here erupts with a blanket of colourful flowers it is a pretty awesome sight. It’s hard to predict exactly when this will occur – it relates to the El Niño/La Niña weather cycles that bring higher volumes of rainfall – but there was a particularly incredible display in September and October 2015 after a massive rainfall in March of that year.

Image credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Frozen “waves”

15/35WHERE: Antartica

WHEN: Year-round

These huge structures look like massive waves right before a surfer disappears into the barrel – only they never break. They are compacted masses of snow that have been pressurised, frozen in time to form these towering, wave-like beauties. Seeing these is all about luck: you'll have to be aboard cruise ship visiting Antarctica that's in the right place at the right time.

Image credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Magnetic termite mounds

16/35WHERE: Northern Territory, Australia

WHEN: Year round

The magnetic termite species found in northern parts of Australia build their own skyscrapers in the form of flat, sand structures that are about two metres in height and all with the exact same north-to-south alignment. Hundreds of them can be viewed inside Litchfield National Park, around 120 kilometres outside of Darwin.

Penitentes

17/35WHERE: Chile and Argentina

WHEN: Year-round

These tall, thin spikes of snow, ranging from one to four metres in height, cover the mountain tops of the Dry Andes mountain region in Chile and Argentina. They are formed via a process of sublimation, in which water vapours in their gaseous form skip the liquid state and turn straight into solid ice. Several day-long tours leave from Mendoza city.

Morning Glory cloud

18/35WHERE: Gulf of Carpentaria, Australia

WHEN: September to November

This astonishing cloud formation looks like shockwaves in the sky. The exact cause is unknown but some meteorologists believe their appearance relates to the different weather systems from central and northern Australian meeting in the Gulf of Carpentaria. The best spot to see one is Burketown in northern Queensland.

Image credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Moskstraumen maelstrom

19/35WHERE: Norway

WHEN: July to August

Maelstroms are systems of tidal whirlpools. One of the most famous examples, and the second most powerful of its kind, is the Moskstraumen system, which is located off the Lofoten Islands on the mid-north coast of Norway. The best way to see it – from a safe distance – is on a private boat tour during peak season.

Periodical cicadas

20/35WHERE: North America

WHEN: May to June in emerging years

Periodical cicadas (often referred to as locusts) found in dry forested areas in the central and eastern parts of North America, spend up to 17 years feeding underground until they dramatically appear by the billions to climb the closest tree, shed their skin and shift to winged form. They fly, engage in a mating process, lay eggs and then … die. You'll have to be lucky to catch them.

Salmon run

21/35WHERE: North America

WHEN: May to September

Every year hundreds of millions of salmon travel from the ocean back to the streams to give birth to a new generation. It’s an absolutely frenetic migration that ends in the death of the salmon and a mass of food for the other wildlife. Natural World Safaris, operating out of Alaska, offers trips that allow visitors to view the salmon run by boat, and, if you’re brave enough, hop into the river and walk among them.

Snow “chimneys”

22/35WHERE: Mount Erebus, Antarctica

WHEN: Year-round

Antarctica’s Mount Erebus is the earth’s southernmost active volcano. As hot gases try to escape from its sides, they push out to form caves, and once the gas actually escapes the caves it forms into tall columns that look like chimneys made of snow. They seem cartoonish but the volcanic gases puffing out the tops are lethal. Some tours include Erebus is their Antarctica itineraries but the stop is completely dependent on the day's conditions.

Sardine run

23/35WHERE: South Africa

WHEN: May to July

South Africa’s sardine run, another mass marine migration, is a phenomenon with no real explanation. After completing their spawning in the cooler waters around South Africa’s Cape, millions of shiny little sardines make their way up the east coast and then disappear from sight. Witness the migration from above water on a tour boat, spot the shimmering patches in the sea from the coast or go below and dive or snorkel among them.

Staircase to the Moon

24/35WHERE: Broome, Australia

WHEN: Three nights per month

As the full moon rises, light reflects off mudflats in Roebuck Bay, creating an optical illusion of stairs reaching up into the night sky. This occurs on three consecutive days of each month when the moon is full – the Broome Visitor Centre publishes the exact dates and times for viewing.

Image credit: Getty Images/iStockphoto

Lake Natron

25/35WHERE: Tanzania

WHEN: September to December

Lake Natron, a shallow pink-hued lake with surface patterns like cracked clay, is a sight in its own right. What makes it even more special, however, is that up to three-quarters of the world’s population of lesser flamingos (the smallest species of flamingo) are born here each year. There are several lodges and campgrounds nearby; and several tour operators stop at Lake Natron on safaris.

Leatherback sea turtle nesting

26/35WHERE: Trinidad and Tobago

WHEN: March to August

When thousands of 250-kilogram reptiles swim across the ocean to dig holes on a beach you know you’re in must-see territory. Leatherback sea turtles (they are the only species without a bony shell) are the world’s largest living turtles and they travel to Trinidad’s beaches where they each lay hundreds of eggs every year. Now comes the cute part: when the tiny little turtles emerge from the sand they all waddle about on the beach trying to find the water. The turtle-watching season runs from March until August – you’ll witness the nesting and laying of eggs at the beginning of this period and the hatching typically starts in June.

Wildebeest migration

27/35WHERE: Kenya and Tanzania

WHEN: January to April

This is it, the most fantastic and overwhelming animal migration on the planet – each year a thunderous herd of more than one million zebra, wildebeest and antelope make their way around the Masai Mara and Serengeti. To be in the right place at the right time, book with a specialist operator.

Image credit: Kei Nomiyam

Rainy season fireflies

28/35WHERE: Shikoku, Japan

WHEN: May to July, between 7:30pm and 9pm

In the forests of Shikoku, multitudes of fireflies appear during Japan’s early-summer rainy season. As many as 50 species of fireflies call the waterways, parks and forests of Japan home, though not all are bioluminescent. Emerging after sunset to captivate visitors and, more pressingly, a mate, the fireflies exist for a brief but glorious few weeks.

Mendenhall Glacier

29/35WHERE: Alaska, United States

WHEN: Year round, best time to visit is May to October

From a distance, the Mendenhall is like any other glacier – a vast mass of ice drifting in slow motion over land. Up close, however, it tells a different story – of a thin, steady stream of water that ripples through it, creating enormous caves with ice-blue ceilings. You can wander into this frozen cathedral on foot or hop on a kayak to float under the almost 21-kilometre-long glacier, about 20 minutes drive from the Alaskan capital of Juneau.

Image credit: Getty Images/Cavan Images RF

Reynisfjara Beach

30/35WHERE: Vík, Iceland

WHEN: Year-round, May to August for puffins and mid-September to mid-April for the Northern Lights

For thousands of years, the ferocious Atlantic Ocean has been whipping the coast of southern Iceland, eroding its ebony volcanic cliffs and turning them to dust – or black sand – that now carpets the beach. Not everything has been diminished by the waves, though. Thousands of basalt columns still stand sentinel to this timeless tussle between land and sea. It’s a striking juxtaposition – frothy white waters, dark obsidian sand and stern soaring cliffs holding their own against the sheer force of the ocean.

Tykky

31/35WHERE: Lapland, Finland

WHEN: January to February

During winter, spruce trees in Finnish Lapland’s Riisitunturi National Park look like commuters snap-frozen in transit. More snow falls here than in any other part of Finland, the most heavily forested country in Europe. Snowshoeing or cross-country skiing to witness these sculptural marvels, the ice coats are known in Finnish as tykky or tykkylumi, isn’t the only reason to visit: the Northern Lights can also make a spectacular appearance.

Wave Rock

32/35WHERE: Hyden, Western Australia

WHEN: Year-round

350 kilometres south-east of Perth lies this dramatic cliff face. The passage of water from seasonal springs nearby has helped shape the granite, each drop chipping away over an estimated 2700 million years to create a tiger-striped contour that reaches 15 metres high – or nearly five storeys – and stretches about 110 metres in length. Visitors to Wave Rock Wildlife Park can wander along the barrel of the wave or follow a walking trail that leads to the crest. To the Noongar people, the traditional custodians of the region, this was a dancing ground. And still today this rock rolls on.

Image credit: Getty Images/iStockphoto

Sailing stones

33/35WHERE: California, United States

WHEN: Year-round

For years the mysterious movement of stones – some as large as a microwave oven – at Racetrack Playa in Death Valley National Park confounded visitors and scientists alike. With nobody having witnessed rocks gliding through the desert, the only proof of the curious event were the trails they left behind, sometimes more than 400 metres long. Extraterrestrial activity is a popular theory. Six years ago, researchers claimed to have cracked the case: as frozen rainwater melts in the heat of the day, it breaks into sheets of ice that are propelled forward by winds, pushing the rocks along the desert floor. But believing in aliens is more fun.

Snow “doughnuts”

34/35Officially known as snow rollers, these doughnut-shaped snow formations require a very precise consistency of snow and just the right amount of gravitational or wind-powered push. If this occurs, snow rolls into massive shapes, like icing-sugar-sprinkled doughnuts. There’s no guarantee where or when they’ll form, though they’re most common in slightly hilly and open areas. They’re super rare, so if you do see one, take all the pictures your phone can hold and then buy a lottery ticket.