An Adventure through Mongolia’s Gobi Desert

The Gobi Desert is a panorama of emptiness. To the south, a golden ribbon of sand lies below dark torn-paper-edge mountains. North is nothing but cracked earth and juniper scrub all the way to the Mongolian steppe. So I’m literally the funniest thing for hundreds of kilometres.

“Waah!” I say, or maybe it’s “Argh!” Something equally erudite, anyway, as the carpet beneath me lurches skywards. I fling an arm around the front hump of the camel as its legs assemble like a folding table: knees first, then the back, then the front.

My guide, Doydoo, cackles merrily from a safe distance. It’s the first time in three days I’ve heard him laugh. The nomads are chuckling, too. Then one grabs the camel’s nose line, coaxes it into motion and we set forth into the vast nothing.

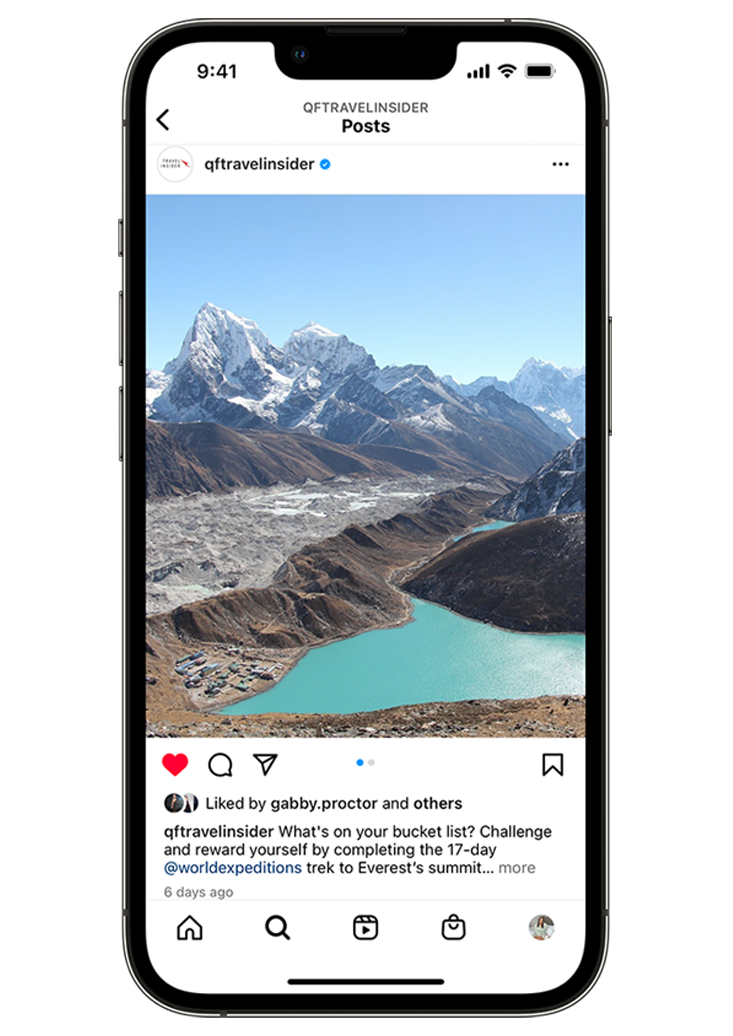

Nothingness is a key feature of Mongolia. The country consists mainly of sky doming expansively over the arid earth. It’s what draws me to the Gobi region: the uninterrupted grandeur of space. In a world compressed by connectivity, I want to regain my sense of scale.

The Gobi sweeps across Mongolia’s southern border from China. It’s not a safety-rail-and-signboard kind of place. Who is out there to post warnings? Who is there to read them? With roughly two people for each square kilometre, Mongolia has one of the lowest population densities on the planet. And even this understates its emptiness, as nearly half the population lives in the capital, Ulaanbaatar. The rest is essentially undeveloped, save for scattered mining outposts.

As such, it’s a good idea to travel with a local. The Gobi is more accessible today than ever before. Luxury tours are available with companies such as Nomadic Expeditions and camel trekking is possible with Stone Horse Expeditions & Travel. But I find my guide the traditional way: through a guy who knows a guy.

Donyddorj Nordog grew up herding in the southern Gobi. Like most Mongolians, he usually goes by his nickname, Doydoo. He is quiet, capable and stoic in the face of my hit-and-miss Mongolian language skills (he speaks only a few words of English). All he packs for our trip is a knife, cigarettes and a battered green petrol can.

It’s June, which, to my mind, is the best time to travel here – after the erratic spring weather but before the tourism rush for the Naadam festival in July. We take a rare paved road south from Ulaanbaatar. Seven hours later, the asphalt runs out at a dusty town, Dalanzadgad, and Doydoo steers our vehicle into the desert.

The Gobi is not a coherent landscape. It changes often, abruptly, like the flipping pages in a book: gravelly scrubland, cracked red dirt, jagged mountains with ibexes hiding in their heights. Dust devils spin lazily in and out of existence. Occasionally we see the golden swirl of an eagle taking off but more often it’s enormous hunchbacked vultures congregating around an unseen meal. Sometimes, in the distance, I glimpse the white thumbnail curve of a herder’s tent.

Spend too much time in this landscape and you begin to suspect you’re participating in something epic. Maps only make it worse, littered with Tolkienesque names like the Flaming Cliffs (Bayanzag), the Singing Sands (Khongoryn Els) and the Valley of the Vultures (the eternal glacier at Yolyn Am).

Doydoo, who takes the same ultralight approach to conversation as packing, indicates a notable site by stopping for a smoke. Every so often he drops a word or two of English, his demeanour so understated that I misunderstand the depth of his knowledge.

“Dinosaur,” he observes at the red cliffs of Bayanzag. No kidding, I think. UNESCO describes the Gobi as the world’s largest reservoir of dinosaur fossils; the first scientifically recognised dinosaur eggs were discovered in these hills in 1923. Doydoo casually flips over a rock, revealing a bone embedded in the rust-coloured surface.

“Picture,” he says the next day, pointing up at a nameless cliff face. Thinking it’s a photo spot, I grab my camera and slog to the top. The ground is scattered with black rocks and I almost stumble on one before noticing the petroglyphs scratched into its surface. These Bronze Age carvings of horses, hunters and curly-horned ibexes lie unremarked in the desert sun.

At sunset, we pull up to a camp of nomadic herders on the edge of the Khongoryn Els, a 100-kilometre-long wave of huge, powdery dunes. The sky’s colour is draining and the sand shifts from gold to pink. Dark shapes roam the edges of the view. “Camels,” remarks Doydoo with the foreshadowing of a smile.

Ganbold, one of the camel herders, sits cross-legged on the carpet as his daughter pours salted milk tea. He points to a tapestry depicting a glowering moustachioed warrior. “Chinggis Khaan,” he says. Then directing his finger to his own T-shirt, “Chinggis Khaan’s baby!” He rocks back and forth laughing, delighted by his lineage. The ancestor in question is known elsewhere as Genghis Khan, founder of the Mongol Empire and the country’s biggest hero. Many Mongolians claim to be descended from his Golden Family. This isn’t as far-fetched as it sounds – a 2003 study suggested that eight per cent of the region’s men are genetically linked to the Great Khan.

Ganbold is less intimidating than his ancestor. His fractured English is held together by an enormous smile as he urges us to drink tea. This easy hospitality belies the fact that as a camel herder in the Gobi Desert, he is as tough as any member of the Great Khan’s horde.

Like most Mongolian nomads, Ganbold’s family lives in a domed tent called a ger. The plain exterior hides a cosy family room with orange painted furniture, framed photographs, beds heaped with pillows and a wood-burning stove for cooking and heat. The Khongoryn Els is their summer home. In winter, when temperatures plummet to -30°C and below, they move their ger to the frozen mountains, chasing snowfall to water their herds.

We sit to the left of the door, the side reserved for guests. Ganbold’s daughter, Uunee, brings heaped plates of tsuivan, stir-fried noodles with mutton. She’s an energetic talker with plenty of English at her disposal but it flies past me in an accented blur.

Gradually, I realise the topic of conversation is my own dubious pronunciation. It seems I’ve introduced my husband as my dog. Before my ego can recover, Uunee changes the subject: “Let’s go riding tomorrow.”

Turns out I’m not a natural camel rider. This isn’t a surprise. Bactrian camels have been domesticated in the Gobi for more than 4000 years; I’ve been here 72 hours. The only desert skill I’ve had time to cultivate is slapstick.

But Uunee isn’t on an adventure; the Gobi is her home. The next morning, after we say our goodbyes, this descendent of the Great Khan leaps onto a camel like she was born to it – which, of course, she was. The last I see of her, she is a silhouette against the dunes, back straight, hair loose in the hot wind. She looks, frankly, epic.

SEE ALSO: Explore the Untamed in Mongolia

Capital gains

Almost every trip to Mongolia begins and ends in its capital, Ulaanbaatar (UB for short). As the major city in a land of nomads, UB is the focal point for music, art and shopping. The night-life is lively and there’s an increasingly diverse international food scene. Here’s a quick guide.

Getting around

Every car in UB is a potential taxi. Extend your arm, palm down, to hail a ride. There’s no bargaining – the accepted rate is 1000 tugriks (about AU$0.50) per kilometre.

Stay

An icon of UB’s skyline, the sailboat-shaped luxury Blue Sky Hotel and Tower overlooks the Soviet-era Sükhbaatar Square.

Eat and drink

Traditional Mongolian food is heavy on meat and light on vegetables. Try a variety of dishes at Modern Nomads, which has venues throughout the city. Enjoy rooftop dining at Terrazza, a Mediterranean restaurant with a sparkling view of UB at night, or head to sister eatery Veranda, which has a similar menu, in the heart of town. Try a range of local beers, including Golden Gobi, at RePUBlik, one of several trendy bars on downtown Seoul Street.

Do

Before travelling to the Gobi, visit UB’s Central Museum of Mongolian Dinosaurs (L. Laagan’s Street), which specialises in repatriated fossils. A daytrip to Gorkhi-Terelj National Park reveals a lusher side to Mongolia with green forests and hills, famous rock formations and a remote Buddhist temple. On the way, stop at the staggeringly huge equestrian statue of Genghis Khan, which has a museum exploring the history of the Mongol Empire inside its base.