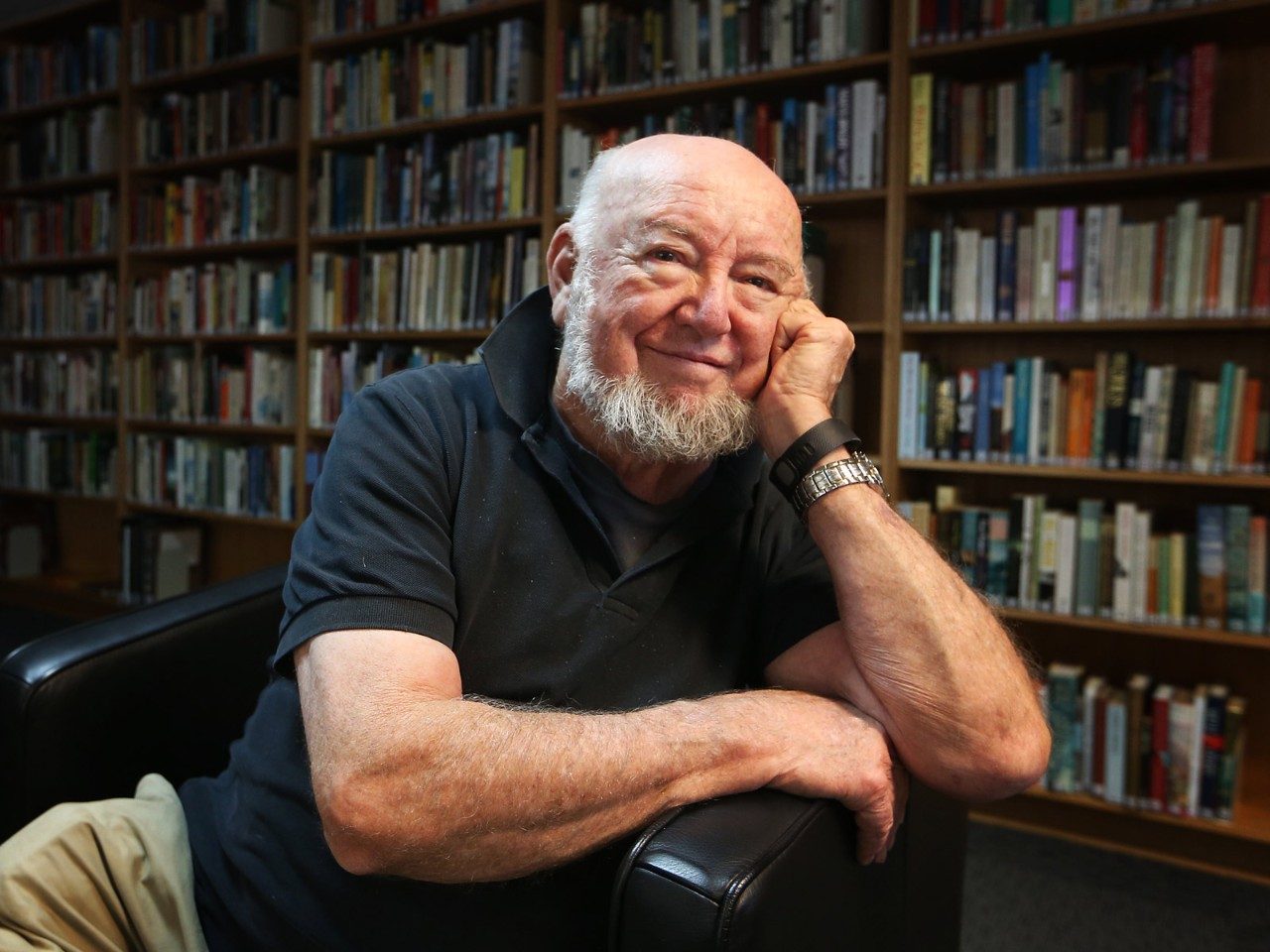

Author Tom Keneally Shares His Memories of Africa

Visits to war-torn Africa delivered some life-affirming moments for the acclaimed Australian author.

Many years ago, I met a young man, Fessahaie, who was from Eritrea in north-eastern Africa. Since 1961, Eritrea had been mired in a war of independence against Ethiopia and this genial and persuasive fellow raised food and other relief and ran it into his besieged country. Fessahaie had persuaded famous Australian eye doctor Fred Hollows to visit and, learning that I’d been discussing the war’s role in the East African famine with some aid agencies, offered to arrange a research visit for me, if I were willing to go.

Everyone who’d been to Eritrea spoke of it as a sort of moral North Pole; a society that was brave, adaptable and inventive. But I was a cosseted, citified Australian with a neurotic streak broader than the Murray. And plane journeys were only the start. Nevertheless, I flew to Rome and connected with a flight to Khartoum, in Sudan. There, I got my permits – to own a camera, to travel to Port Sudan – but never, my Eritrean minders told me, should I admit that I was going into Eritrea.

Planes to Port Sudan, on the Red Sea coast, were infrequent, there was no seat allocation and many passengers carried swords that had to be stacked in the loo. In Port Sudan, I was taken by truck, in a convoy of Australian and American wheat, through a magnificently desolate quarter of Sudan and into the mountains in Eritrea. We travelled by night to avoid daytime bombing missions.

In Eritrea, I was out of my depth the entire time, overwhelmed by the scale of the war. Like Fred Hollows, I was awestruck by the hospital in Orotta where, in containers dug into hillsides, operations on sick and wounded Eritreans began when the generators came on at dusk. The Eritreans were determined not to be a hapless, dependent people. They manufactured antibiotics there, as well as their own saline drips and surgical infusions.

I remember a dreamlike range of experiences from that first visit... The wedding of a male bureaucrat and a female fighter in a tent where people clapped and shrilled and we drank beer made from scraps of injera (flatbread). Abandoning our broken-down truck and hiding reflective watches and glasses in our pockets when an Ethiopian reconnaissance bomber flew overhead. Being fetched up in a cave where a rebel Eritrean congresswoman was breastfeeding her newborn. A football match attended by young Eritrean fighters one lovely dusk near the ruined town of Nakfa. The wife of the town administrator emerging from the bunker next door to mine to call her four-year-old daughter inside before the afternoon shelling began. The first wounded woman I saw, a limpid-eyed 19-year-old rebel, whose body was shattered. Where is she now and all the others I saw on my four trips to Eritrea (two with my brave wife, Judy)?

Fred Hollows, no fool, backed the Eritreans. “These people give it a go,” he growled, “and they’re not bloody tea-leaves.” The people won the revolution but were betrayed, after so much loss, by their leaders. Now, in every shipload of refugees attempting to cross the Mediterranean, there are Eritreans. They deserve a better destiny and I wish them it and thank them for all their mercies to the hapless traveller I was.

SEE ALSO: Richard Fidler on the Journey That Changed Him