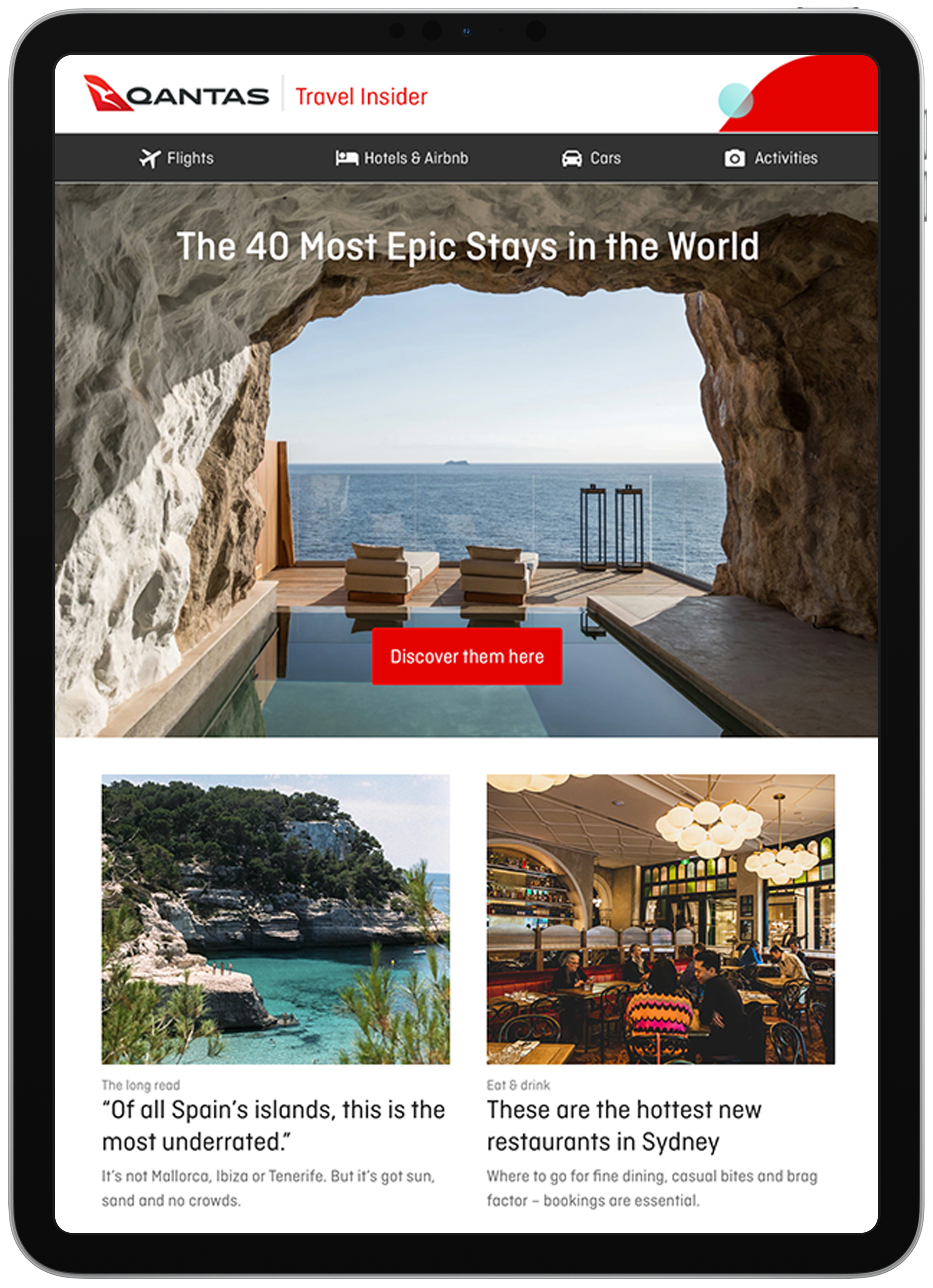

Why Tasmania's Saffire Freycinet Should Be Your Next Stay

Not even the rain can bring things to a stand still in this corner of the Apple Isle where time marches on. Kirsten Galliot shares why Saffire Freycinet is the most magical way to experience Tasmania.

Fifty years ago, the spot where I’m standing used to be a caravan park. Hundreds of years ago, Palawa women swam off the beach, holding their breath for up to nine-and-a-half minutes as they dived for prized abalone. Thirty-five thousand years ago, First Nations people would travel down to this area from the mainland – there was no Bass Strait then – to hunt Bennett’s wallabies when the sun was warm and the grass was plentiful.

Now this patch of land on Tasmania’s east coast is home to one of Australia’s most luxurious retreats, Saffire Freycinet, and the juxtaposition of past and present feels sensitive. The graceful curve of the resort’s roof blends into the natural environment. The 20 suites are dwarfed by the mighty Hazards, the imposing mountain range that glows magnolia-pink at sunset. The bedtime story that waits on my pillow recounts the history of the Great Oyster Bay people.

I know none of this when I arrive, of course. I’m too wowed by the surroundings. The Private Pavilion in which I’m staying – one of four on the property – has a plunge pool in the courtyard and a bed that looks across to the Hazards, Freycinet Peninsula and Great Oyster Bay. It’s the kind of space that begs you to sit in the chair by the window and contemplate place and connection.

That’s if I have time. Saffire offers a plethora of signature experiences – from cruises in Wineglass Bay to fly fishing – that incur an additional fee, as well as complimentary activities like beekeeping, guided kayaking and an encounter with Tasmanian devils. I’ve signed up for a Wineglass Bay by Water boat trip and a coastal stroll with Mick Quilliam, who runs the Connection to Country tour. And I’m all set for Saffire’s famous oyster experience, which will see me throw on a pair of waders and slurp briny Pacifics in the middle of a river.

But when I wake up the next morning it’s raining. There’s so much rain it’s as if The Hazards disappeared overnight. Patrick, the resort’s disarming guide manager, has the unenviable task of dealing with both the weather and the expectations of guests who have paid upwards of $2300 a night to experience all that the Freycinet Peninsula has to offer.

You find out what a high-end retreat is made of in conditions like this. At breakfast, Patrick goes from table to table, empathising with guests and seamlessly swapping cruises for indoor activities and reconfiguring the oyster experience. “We’ll bring the marine farm experience into Saffire Freycinet,” he says with a smile. “We’ll have a marine biologist onsite. It’s a different experience but we do our best.”

The rain doesn’t dampen my spirits – or interrupt my plans to meet up with Quilliam, a Palawa man and local artist. He used to stay at the caravan park when he was a toddler and lives in nearby Bicheno. “The more I connect with the land, the stronger it makes me mentally,” he says as we walk in the resort’s native gardens, shielded by over-sized umbrellas. “My grandmother taught me what she knew and I’ve been learning ever since. Now I put what I know onto canvas.”

Quilliam is an enthusiastic, engaging companion, pulling strips of pale rush from the ground and twisting them between his fingers as he paints evocative pictures of the past. He describes dome houses made of whale bones and boats wrapped in paperbark. “This is the only area in Tasmania where we used catamarans to get us up and into the lagoons.”

He takes me back further still, to the Ice Age, when there was no rain like that falling around us now. “We had the practice of ‘little drink’,” he explains. “We learnt how to survive without drinking.” He revisits the time when Tasmanian Aboriginal people used kangaroo tendons to make string and sewed the skins of eastern grey kangaroos together to make long, winter coats.

He pulls a long, bone-like needle out of his bag. “What do you think this is?” I offer up a feeble guess. “It’s an echidna quill! It’s the same material as a fingernail. Echidnas are really oily and good to eat. You just wrap them in clay and put them over the coals. Delicious!”

There’s no echidna on the menu at Saffire but there’s plenty of seafood – oysters, scallops, calamari and black mussels – as well as local beef and Springfield venison from the north of Tasmania. All food and drink is included in the tariff – as well as some cracker island wines, such as Stargazer riesling and Marco Lubiana pinot noir – and there’s a very generous minibar so there’s no chance of going hungry.

After a three-course lunch featuring a very pretty quail and beetroot salad with toasted walnuts, I hardly need more food but I’m keen to get an understanding of the oyster farm experience and, as Patrick promised, Shea is waiting for me in the Lounge. “This is what we call a bespoke experience,” she says, laughing as she gestures to the mountain of oysters waiting for me. “It’s unlike anything else.”

In fine weather, guests drive along the Swan River to Freycinet Marine Farm, where they tour the production facilities before wading into the river to eat oysters on a white-clothed table, surrounded by water. I sit in the comfort of the Lounge, as the rain pounds the windows, eating more oysters than I thought possible and drinking as much of the local Kreglinger sparkling as I want.

Freycinet Marine Farm produces 3.5 million oysters a year, which are only sold at their shop front, the nearby Devil’s Corner cellar door and to Saffire. The water conditions here aren’t conducive to pearl production, explains Shea, but they’re ideal for fat, creamy Pacific oysters, which “are grown in the flowing water”.

The process is lengthy. Oysters spawn in the summer and build themselves a shell. “They grow on the broken shells of old oysters and absorb those flavours,” says Shea, who adds that when the Pacifics get to about 55 millimetres, they go out to deep water to “fatten up” before going back into the river. “The oysters we’re eating are two to three years of age; these were taken from the water yesterday.”

She shucks me another Pacific. It tastes of the sea and I think of the Palawa women, tossing the shells onto the sand and creating the middens we see today. It hasn’t been the trip I expected. The rain put paid to that. But I have a much deeper understanding of the connection with the land. I’ve eaten incredible food and enjoyed amazing wine. And I now have time to sit on that chair in the corner, look out at the lightening sky and think about all I’m seeing.

Start planning now

SEE ALSO: Your Ultimate Guide to Visiting the Freycinet Peninsula

Image credit: Adam Gibson